|

|

|

|

| Called Third Strike .... Your Outta Here.... |

|

| Sorry , No Dropped Third Strike Here Mr. Umpire |

"Injustice fights with two weapons, force

and fraud ... A common form of injustice

is chicanery,

that is, an oversubtle, in

fact a fraudulent construction of the law."

Cicero - On Moral Duties

For those of you who may find this site disorganized

remember and be glad that none of this happened to you.

Most of the material that should be here for various reasons, is not.

Some will never be added to this site, and some will

be added when it becomes appropriate.

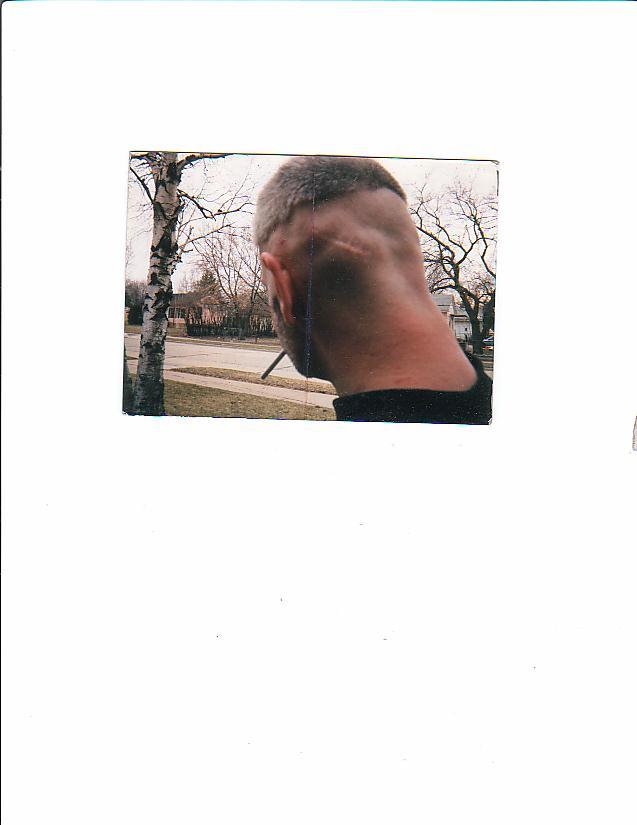

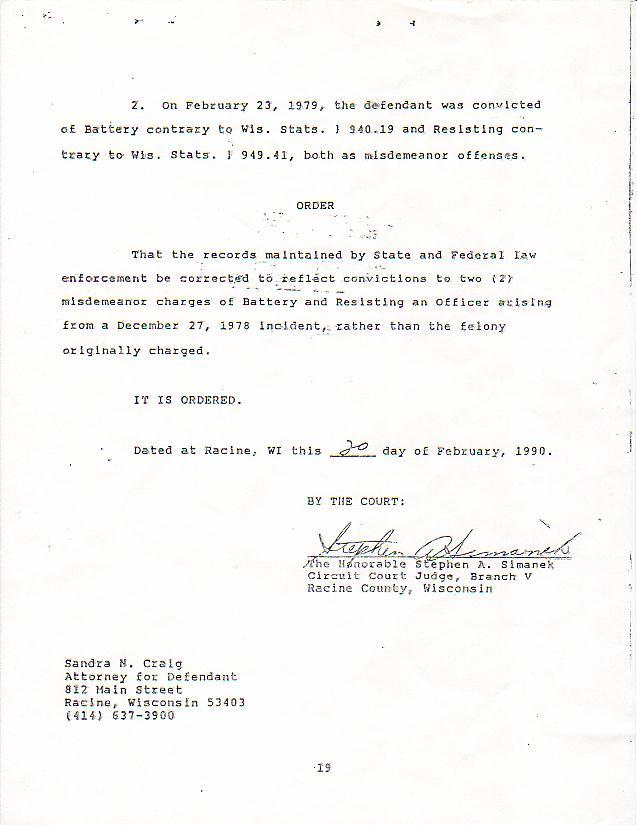

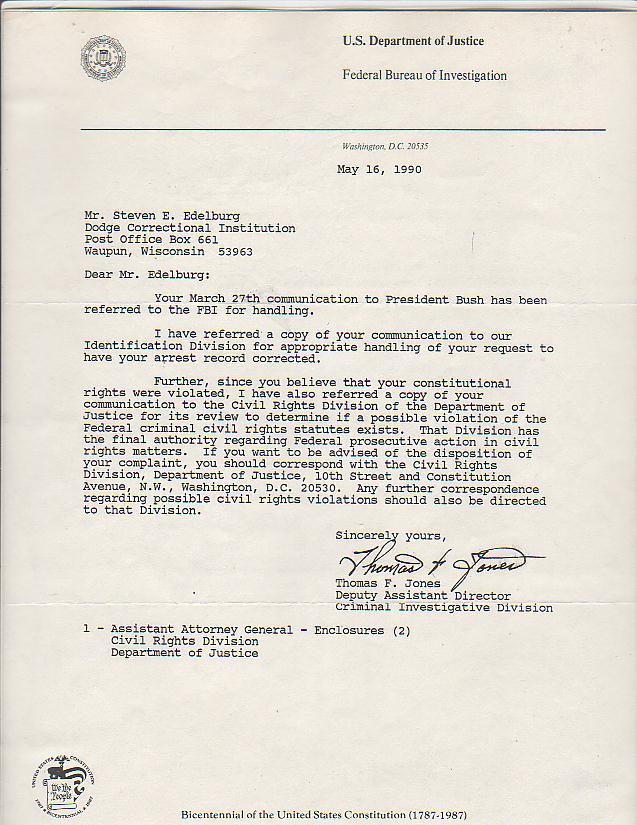

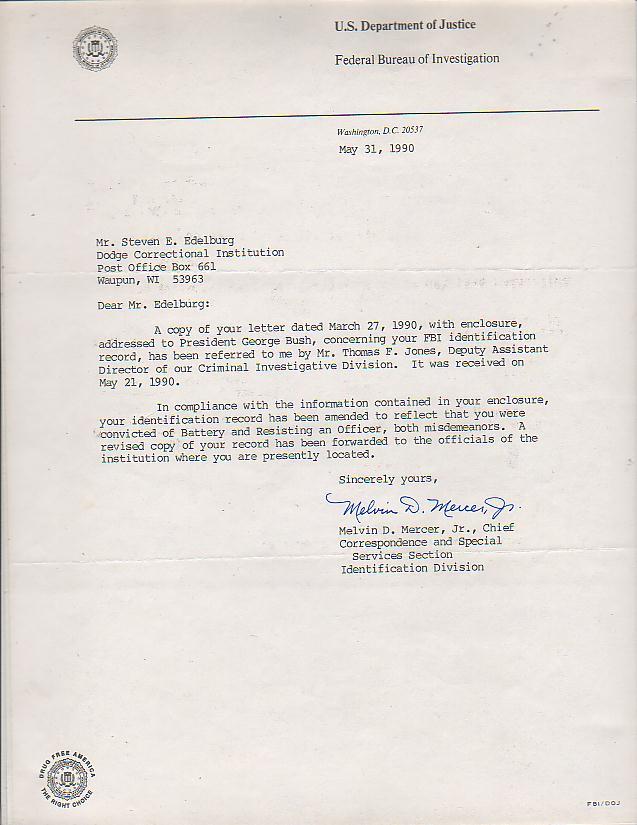

The following pictures are of my head and neck injuries and the 12 years of being a convicted felon without that being

true it should also be noted these are not the only lies I've had to endure and other people have been hurt because of this

dishonest and corrupt situation that grows everyday

Please understand that almost immediately after this 1978 incident the manipulation started

example: the backing up of the court date, this

was accomplished by stating it would be better

for "Steven" if he waited for a certain party to be

out of the District Attorney's office.... meantime

the injuries to arms, neck and head became

less noticeable with the hair hiding the worst

part of it.

FRAUD: "An intentional perversion of the truth for the purpose of inducing another in reliance upon it to part with some valuable

thing belonging to him or to surrender a legal right; a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct,

by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended

to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury."

Black's Law Dictionary

CIVIL CONSPIRACY - 'The elements of an action for civil conspiracy are the formation and operation of the conspiracy and damage

resulting to plaintiff from an act or acts done in furtherance of the common design. . . . In such an action the major significance

of the conspiracy lies in the fact that it renders each participant in the wrongful act responsible as a joint tortfeasor

for all damages ensuing from the wrong, irrespective of whether or not he was a direct actor and regardless of the degree

of his activity.'' (Doctors' Co. v. Superior Court (1989) 49 Cal.3d 44, citing Mox Incorporated v. Woods (1927) 202 Cal. 675,

677-78.)' (Id. at 511.)

'Conspiracy is not a cause of action, but a legal doctrine that imposes liability on persons who, although not actually

committing a tort themselves, share with the immediate tortfeasors a common plan or design in its perpetration. By participation

in a civil conspiracy, a coconspirator effectively adopts as his or her own the torts of other coconspirators within the ambit

of the conspiracy. In this way, a coconspirator incurs tort liability co-equal with the immediate tortfeasors. Standing alone,

a conspiracy does no harm and engenders no tort liability. It must be activated by the commission of an actual tort. ''A civil

conspiracy, however atrocious, does not per se give rise to a cause of action unless a civil wrong has been committed resulting

in damage.'' 'A bare agreement among two or more persons to harm a third person cannot injure the latter unless and until

acts are actually performed pursuant to the agreement. Therefore, it is the acts done and not the conspiracy to do them which

should be regarded as the essence of the civil action.' [para.s] By its nature, tort liability arising from conspiracy presupposes

that the coconspirator is legally capable of committing the tort, i.e., that he or she owes a duty to plaintiff recognized

by law and is potentially subject to liability for breach of that duty.' (Allied Equipment Corp. v. Litton Saudi Arabia Ltd.,

supra, 7 Cal.4th at 510-11.)

Bureaucracy defends

the status quo

long past the time

when the quo

has lost its status.

LAURENCE J. PETER

Propagandists:

wield words

as nonviolent offensive

and defensive weapon system

that publicize,

conceal,

or misrepresent

the real source

to set stages properly,

exploit successes,

minimize failures,

and make the most of mixed results.

Cohesive programs,

which put collective "good" above self-interest,

solicit compliance and collaboration,

whether the objective is stability or subversion.

Divisive programs,

conversely,

seek to seperate individuals from groups and

groups

from each other or society at large.

Apathy,

panic,

disobedience,

desertion,

and surrender are typical objectives.

Psychological Operations:

may precede,

accompany,

replace,

or, follow applications of force,

constitute the planned use of propaganda

and physical action ( terrorism )

to influence the behavior of:

friendly,

enemy,

or neutral audiences

in support of politico-military aims.

Psyop Specialists:

target people who share predispositions.

Psyopers must master:

political,

economic,

cultural,

and topical subjects,

before they can skillfully tailor themes

to acquire and sustain attention of particular

target groups ( audiences ) and effectively

refute counter efforts.

EXCERPT FROM: U.S. AND SOVIET OPERATIONS

BY JOHN M. COLLINS, SENIOR SPECIALIST

IN NATIONAL DEFENSE, 23 DECEMBER 1986.

Subversion:

seeks to undermine the morale

and transfer the allegiance of

specific groups.

Disinformation commonly assists.

Competent employers not only make it seem

reasonable, but difficult for the duped to

ascertain the truth if they try.

Statements out of context,

unfair comparisons,

false alarms,

smear tactics,

oversimplified slogans,

and skewed cause/effect relationships

are representative techniques.

The best defense against psyops depends on

variables, but three rules of thumb seem

evident:

1) silence provides rivals little

incentive to desist ( stop );

2) vague rebuttals rarely are

beneficial;

3) hyperbole often boomerangs.

A steady flow of truthful information, which

most Americans advocate, is not automatically

the antidote for disinformation, because truth

can hurt as well as help.

EXCERPT FROM:

U.S. AND SOVIET SPECIAL OPERATIONS,

BY JOHN M. COLLINS. SENIOR SPECIALIST

IN NATIONAL DEFENSE, 23 DEC 1986.

Title 18 U.S.C § 1510. Obstruction of criminal investigation.

(a) Whoever willfully endeavors by means of bribery to obstruct, delay, or prevent the communication of information relating

to a violation of any criminal statute of the United States by any person to a criminal investigator shall be fined not more

than $5,000, or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 1512. Tampering with a witness, victim, or an informant

(b) Whoever knowingly uses intimidation or physical force, threatens, or corruptly persuades another person, or attempts to

do so, or engages in misleading conduct toward another person, with intent to–

(1) influence, delay, or prevent the testimony of any person in an official proceeding;

(2) cause or induce any person to–

(A) withhold testimony, or withhold a record, document, or other object, from an official proceeding;

(3) hinder, delay, or prevent the communication to a law enforcement officer or judge of the United States of information

relating to the commission or possible commission of a Federal offense ... shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not

more than ten years, or both.

(c) Whoever intentionally harasses another person and thereby hinders, delays, prevents, or dissuades any person from–

(1) attending or testifying in an official proceeding;

(2) reporting to a law enforcement officer or judge of the United States the commission or possible commission of a Federal

offense ... (3) arresting or seeking the arrest of another person in connection with a Federal offense; or

(4) causing a criminal prosecution, or a parole or probation revocation preceding, to be sought or instituted, or assisting

in such prosecution or proceeding;

or attempts to do so, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.

(e) For the purposes of this section–

(1) an official proceeding need not be pending or about to be instituted at the time of the offense; and

(2) the testimony, or the record, document, or other object need not be admissible in evidence or free of a claim of privilege.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 1513. Retaliating against a witness, victim, or an informant.

(a) Whoever knowingly engages in any conduct and thereby causes bodily injury to another person or damages the tangible property

of another person, or threatens to do so, with intent to retaliate against any person for (1) the attendance of a witness

or party at an official proceeding, or any testimony given or any record, document, or other object produced by a witness

in an official proceeding; or (2) any information relating to the commission or possible commission of a Federal offense ..."

Title 18 U.S.C. § 111. Impeding certain officers or employees. Whoever ... intimidates, or interferes with any person ...

while engaged in ... the performance of his official duties shall be fined ... or imprisoned ...

Title 18 U.S.C. § 1621. Perjury generally. Whoever (1) having taken an oath before a competent tribunal ... willfully and

contrary to such oath states ... any material matter which he does not believe to be true, he shall be fined ... or imprisoned

...

Title 18 U.S.C. § 1622. Subornation of perjury

Whoever procures another to commit any perjury is guilty of subornation of perjury, and shall be fined under this title or

imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 1341. Frauds and swindles.

Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property by means

of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises, .... for the purpose of executing such scheme or artifice

or attempting so to do, places in any post office or authorized depository for mail matter, any matter or thing whatever to

be sent or delivered by the Postal Service, or takes or receives therefrom, any such matter or thing, or knowingly causes

to be delivered by mail according to the direction thereon, or at the place at which it is directed to be delivered by the

person to whom it is addressed, any such matter or thing, shall be fined ... or imprisoned .... or both.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 1343. Fraud by wire, radio, or television

Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property by means

of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises, transmits or causes to be transmitted by means of wire, radio,

or television communication in interstate or foreign commerce, any writings, signs, signals, pictures, or sounds for the purpose

of executing such scheme or artifice, shall be fined not more than $1,000 or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 245. Federally protected activities.

(b) Whoever, whether or not acting under color of law, by force or threat of force willfully injures, intimidates or interferes

with, or attempts to injure, intimidate or interfere with–

(1) any person because he is or has been, or in order to intimidate such person or any other person or any class of persons

[whistleblowers against corruption in government] from–

(B) participating in or enjoying any benefit, service, privilege, program facility, or activity provided or administered by

the United States;

(C) applying for or enjoying employment, or any perquisite thereof, by any agency of the United States.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 246. Deprivation of relief benefits

Whoever directly or indirectly deprives, attempts to deprive, or threatens to deprive any person of any employment, position,

work, compensation, or other benefit provided for or made possible in whole or in part by any Act of Congress appropriating

funds for work relief or relief purposes, on account of political affiliation [whistleblower] ... shall be fined under this

title, or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 241. Conspiracy against [civil] rights

If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth,

Possession, or District in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or

laws of the United States, or because of his having so exercised the same; ... they shall be fined under this title or imprisoned

not more than ten years.

Title 28 U.S.C. § 2201. Creation of remedy. In a case of actual controversy within its jurisdiction, any court of the United

States, upon the filing of an appropriate pleading, may declare the rights and other legal relations of any interested party

seeking such declaration, whether or not further relief is or could be sought. Any such declaration shall have the force and

effect of a final judgment or decree and shall be reviewable as such.

Title 28 U.S.C. § 2202. Further relief. Further necessary or proper relief based on a declaratory judgment or decree may be

granted, after reasonable notice and hearing, against any adverse party whose rights have been determined by such judgment.

Treasonous Conduct

The definition of treason includes criminal attempts to destroy the lawful existence of government offices; a breach of allegiance,

such as the allegiance to support the laws and Constitution of the United States.

Subversive Conduct

Subversive conduct is conduct that undermines and overthrows established authority of the government. Undermining the foundation

of government. The judicial conduct that subverts the laws and Constitution of the United States, that obstructs justice,

that aids and abets criminal activities, meet this definition.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 2. Principals. (a) Whoever commits an offense against the United States or aids, abets, counsels, commands,

induces or procures its commission, is punishable as a principal. (b) Whoever willfully causes an act to be done which if

directly performed by him or another would be an offense against the United States, is punishable as a principal.

Note: The legislative intent to punish as a principal not only one who directly commits an offense and one who "aids, abets,

counsels, commands, induces or procures" another to commit an offense, but also anyone who causes the doing of an act which

if done by him directly would render him guilty of an offense against the United States. Case law decisions: Rothenburg v.

United States, 1918, 38 S.Ct. 18, 245 U.S. 480, 62 L.Ed. 414, and United States v. Giles, 1937, 57 S.Ct. 340, 300 U.S. 41,

81 L.Ed. 493.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 3. Accessory after the fact. Whoever, knowing that an offense against the United States had been committed,

receives, relieves, comforts or assists the offender in order to hinder or prevent his apprehension, trial or punishment,

is an accessory after the fact.

CONSPIRACY

PINKERTON CHARGE (CONSPIRACY)

- a jury instruction based on the doctrine that each member of a conspiracy is responsible for the actions of other members

performed during the course and in furtherance of the conspiracy. If one member of a conspiracy commits a crime in furtherance

of a conspiracy, the other members have also, under the law, committed the crime.

Legal definition of Conspiracy

Conspiracy. A combination or confederacy between

two or more persons formed for the purpose of committing, by their joint efforts, some unlawful or criminal act, or some act

which is lawful in itself, but becomes unlawful when done by the concerted action of the conspirators, or for the purpose

of using criminal or unlawful means to the commission of an act not in itself unlawful.

A person is guilty of conspiracy

with another person or persons to commit a crime if with the purpose of promoting or facilitating its commission he: (a) agrees

with such other person or persons that they or one or more of them will engage in conduct which constitutes such crime or

an attempt or solicitation to commit such crime; or (b) agrees to aid such other person or persons in the planning or commission

of such crime or of an attempt or solicitation to commit such crime. Model Penal Code, § 5.03.

Crime of conspiracy is

distinct from the crime contemplated by the conspiracy (target crime), Corn. v. Dyer, 243 Mass. 472, 509, 138 N.E. 296, 314,

cert. denied, 262 U.S. 751, 43 S.Ct. 700, 67 L.Ed. 1214. Some jurisdictions do not require an overt act as an element of the

crime, e.g. Corn. v. Harris, 232 Mass. 588, 122 N.E. 749.

A conspiracy may be a continuing one; actors may drop out, and

others drop in; the details of operation may change from time to time; the members need not know each other or the part played

by others; a member need not know all the details of the plan or the operations; he must, however, know the purpose of the

conspiracy and agree to become a party to a plan to effectuate that purpose. Craig v. U. S., C.C.A.Cal., 81 F.2d 816, 822.

There are a number of federal statutes prohibiting specific types of conspiracy. See, eg., 18 U.S.C.A. 371. See also Chain

conspiracy; Co-conspirator's rule; Combination in restraint of trade; Confederacy; Seditious conspiracy; Wharton Rule.

Chain

conspiracy. Such conspiracy is characterized by different activities carried on with same subject of conspiracy in chain-like

manner that each conspirator in chain-like manner performs a separate function which serves in the accomplishment of the overall

conspiracy. Bolden v. State, 44 Md.App. 643, 410 A.2d 1085, 1091.

Civil conspiracy. The essence of a "civil conspiracy"

is a concert or combination to defraud or cause other injury to person or property, which results in damage to the person

or property of plaintiff. See also Civil conspiracy.

Overthrow of government. See Sedition.

Seditions conspiracy.

See Sedition.

Conspiracy in restraint of trade. Term which describes all forms of illegal agreements such as boycotts,

price fixing, etc., which have as their object interference with free flow of commerce and trade. See Antitrust acts; Clayton

Act; Sherman Antitrust Act.

Conspirators. Persons partaking in conspiracy. See Conspiracy.

Conspire. To engage in

conspiracy. Term carries with it the idea of agreement, concurrence and combination, and hence is inapplicable to a single

person or thing, and one cannot agree or conspire with another who does not agree or conspire with him. See Conspiracy.

SOURCE:

Black's Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition

Sec. 1985. - Conspiracy to interfere with civil rights

(1) Preventing officer from performing duties

If two or more persons in any State or Territory conspire to prevent, by force, intimidation, or threat, any person from accepting

or holding any office, trust, or place of confidence under the United States, or from discharging any duties thereof; or to

induce by like means any officer of the United States to leave any State, district, or place, where his duties as an officer

are required to be performed, or to injure him in his person or property on account of his lawful discharge of the duties

of his office, or while engaged in the lawful discharge thereof, or to injure his property so as to molest, interrupt, hinder,

or impede him in the discharge of his official duties;

(2) Obstructing justice; intimidating party, witness, or juror

If two or more persons in any State or Territory conspire to deter, by force, intimidation, or threat, any party or witness

in any court of the United States from attending such court, or from testifying to any matter pending therein, freely, fully,

and truthfully, or to injure such party or witness in his person or property on account of his having so attended or testified,

or to influence the verdict, presentment, or indictment of any grand or petit juror in any such court, or to injure such juror

in his person or property on account of any verdict, presentment, or indictment lawfully assented to by him, or of his being

or having been such juror; or if two or more persons conspire for the purpose of impeding, hindering, obstructing, or defeating,

in any manner, the due course of justice in any State or Territory, with intent to deny to any citizen the equal protection

of the laws, or to injure him or his property for lawfully enforcing, or attempting to enforce, the right of any person, or

class of persons, to the equal protection of the laws;

(3) Depriving persons of rights or privileges

If two or more persons in any State or Territory conspire or go in disguise on the highway or on the premises of another,

for the purpose of depriving, either directly or indirectly, any person or class of persons of the equal protection of the

laws, or of equal privileges and immunities under the laws; or for the purpose of preventing or hindering the constituted

authorities of any State or Territory from giving or securing to all persons within such State or Territory the equal protection

of the laws; or if two or more persons conspire to prevent by force, intimidation, or threat, any citizen who is lawfully

entitled to vote, from giving his support or advocacy in a legal manner, toward or in favor of the election of any lawfully

qualified person as an elector for President or Vice President, or as a Member of Congress of the United States; or to injure

any citizen in person or property on account of such support or advocacy; in any case of conspiracy set forth in this section,

if one or more persons engaged therein do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the object of such conspiracy, whereby

another is injured in his person or property, or deprived of having and exercising any right or privilege of a citizen of

the United States, the party so injured or deprived may have an action for the recovery of damages occasioned by such injury

or deprivation, against any one or more of the conspirators

Sec. 1986. - Action for neglect to prevent

Every person who, having knowledge that any of the wrongs conspired to be done, and mentioned in section 1985 of this title,

are about to be committed, and having power to prevent or aid in preventing the commission of the same, neglects or refuses

so to do, if such wrongful act be committed, shall be liable to the party injured, or his legal representatives, for all damages

caused by such wrongful act, which such person by reasonable diligence could have prevented; and such damages may be recovered

in an action on the case; and any number of persons guilty of such wrongful neglect or refusal may be joined as defendants

in the action; and if the death of any party be caused by any such wrongful act and neglect, the legal representatives of

the deceased shall have such action therefor, and may recover not exceeding $5,000 damages therein, for the benefit of the

widow of the deceased, if there be one, and if there be no widow, then for the benefit of the next of kin of the deceased.

But no action under the provisions of this section shall be sustained which is not commenced within one year after the cause

of action has accrued

Battered Plaintiffs - injuries from hired guns and compliant courts

It is bad enough to suffer an injury at work, or the savage retribution routinely meted out to whistleblowers. But as is well

known in whistleblowing circles, if the injured person then tries to obtain redress through the ‘justice’ system,

they are likely to suffer further injury from the system itself- in some cases, more severe and damaging than the original

one. This is such a problem, at this stage so insurmountable to the great majority of would-be plaintiffs, that my routine

advice to patients wanting to try litigation is basically - "Don’t". However many still do; some really have no choice

but to try; some are caught up with ‘hired guns’ while still employed, forced by the threat of losing their jobs

for refusing to obey a lawful order. (If you want to dispute that the order is in fact lawful, of course you end up in court

anyway.)

Hired guns

Hired gun psychiatrists are covered in more detail in my chapter on bullying in medico-legal examinations, in ‘Bullying,

from backyard to boardroom’ (ed. McCarthy, Sheehan and Wilkie, 1996). There are hired guns in other medical specialties,

but they appear to be most frequent, and most vicious, in psychiatry - probably because, as a ‘soft’ science,

lacking the hard evidence of X-rays and tissue examination, psychiatry is more open to opinions, no matter how outrageous.

This is unfortunate for the victims on two counts: firstly, a psychiatric diagnosis carries a severe stigma in our society,

and however sane the victim may in fact be, some mud can be expected to stick, particularly among their enemies. It is thus

an extremely effective way to discredit the victim together with their complaints, and supposedly confidential reports are

commonly overtly or covertly circulated where they can do most damage. Secondly, a psychiatric examination, on a traumatic

issue, is often traumatic in itself because the patient is compelled to relive the trauma. This is acceptable for the purpose

of therapy, but purely for medico-legal purposes will almost inevitably add another injury to the psyche. If the psychiatrist

is an abusive hired gun, and if the patient is forced by the system, as many are, to see a number of them, the additional

injury can be severe. Also most whistleblowers, and many Workers’ Compensation claimants, do develop psychiatric problems

such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder, for which they will need help, usually from a psychiatrist.

If the trust necessary for an effective therapeutic relationship has been damaged or destroyed by a traumatic earlier encounter

with a hired gun psychiatrist, the effect can be devastating, and a condition that should have been relatively easy to treat

can become crippling.

The two main situations where hired guns are employed are in whistleblowing cases, when the employer wants to discredit and

if possible get rid of the employee; and in Workers’ Compensation cases where the employee is claiming for a psychiatric

injury, and the employer wants to avoid liability. Whistleblowers can, and commonly do, end up in both situations, after the

victimisation and harassment they are subjected to at work in due course causes a major depressive illness. However there

are important differences in the two situations, especially the ‘diagnosis’.

Hired guns in whistleblowing

In this situation the employer will want a diagnosis that ‘proves’ the whistleblower is a nut-case, rat-bag, and

troublemaker; that the issues on which they have blown the whistle can therefore be safely ignored; and they can justifiably

dismiss or medically retire the whistleblower. The diagnosis in that case is almost invariably a paranoid personality disorder

(i.e. the whistleblower has been misinterpreting or imagining both the malpractice and/or corruption they complained about,

together with the harassment and victimisation that almost invariably follow someone making such complaints). Occasionally

the hired gun can stretch the diagnosis to a paranoid illness, such as paranoid schizophrenia. This is uncommon in Australia,

where we don’t (yet) have the convenient diagnosis used in Soviet psychiatry to deal with dissidents there. ‘Creeping’

or ‘sluggish’ schizophrenia was an illness confined to the USSR, with no symptoms apart from the urge to dissent:

"The presence of sluggish schizophrenia does not presuppose noticeable personality changes and the absence of such symptoms

does not prove the absence of the illness itself."

"The morbid process develops very slowly so that its other manifestations remain imperceptible. Diagnostic difficulties increase

if the subject relates in a formally correct way to the environment."

However this lack of symptoms, coupled with ‘reformist ideas’, particularly if expressed with ‘an unshakeable

conviction of his own rightness’ was enough to land dissidents in the nightmare of psychiatric prison hospital, indefinitely,

or until the administration of overdoses of psychiatric drugs and other ‘treatment’ led to the ‘fading away

of delirious conceptions’ - i.e. willingness under that duress to agree to toe the Party line.

In Australia, the diagnosis of paranoid personality disorder has some striking similarities. For this diagnosis to be valid,

a patient must have exhibited symptoms throughout their adult life, and in all areas of it, not just at work. Most whistleblowers

are well above average as employees, and until they blow the whistle have exemplary work records, as well as being unremarkable

in their family and personal lives. That is, there is no evidence to support the diagnosis of a paranoid - or any other -

pre-existing personality disorder, and of course thinking that you are being persecuted once you really are being victimised

is not a sign of mental illness. But just as lack of evidence wasn’t a problem in the USSR, it often presents no problems

here:

"There is no past history of personality difficulties which I am aware of and from a psychiatric point of view I cannot establish

the presence throughout his life of personality traits which significantly affected his work or social life. This is not surprising

given Mr W’s defensiveness and projection of all his difficulties onto the Department."

"I found Mr T. to be very cooperative in the interviews and to have a cheerful and pleasant manner. This contrasted with accounts

given to me by others, mentioned above, that he can at times be very belligerent and uncooperative. It was easy to see that

he would be able to present his viewpoints in a very plausible manner to people who were in relatively brief contact with

him, or who did not seriously challenge his statements."

Hired guns here, like their Soviet counterparts, have problems with the whistleblower’s conviction of his own rightness:

"He has developed compulsive behaviour based on his own set of high moral values.....This type of personality could qualify

as a reason for retirement on medical grounds. If this did occur, it would have to be forced on Mr V, as he can see nothing

wrong with his personality and merely considers himself a person of high integrity."

And with their persistence in pursuing authorities to try to get action on their complaints....

"There is every reason to believe he will continue in his present litigious activities writing numerous letters to parliamentarians,

ministers and the PM etc. He is quite insightless into his mental condition....." "There seems little doubt that in the last

year what had been a highly valued idea by him, that is exposure of corruption in the SRA, has become an obsession in the

sense that he both cannot and will not put it out of his mind..."

And at the ‘overestimation of himself’ that caused problems for Soviet psychiatrists: "He was very grandiose regarding

his abilities as a quarantine officer......." "..he may in fact have a personality disorder. His personality traits are such

as to produce grandiose and obsessive behaviour..."

Hired guns in Workers’ Compensation

In this situation the employee is usually claiming for post-traumatic stress disorder, and the hired gun’s task is to

show that he/she does not or could not have such a condition, despite in some cases the precipitating event having been extraordinarily

traumatic by normal standards, e.g. the Voyager disaster. More details of such reports can be found in the chapter in the

‘Bullying’ book referred to above. In these cases the hired gun, rather than bending over backwards to find symptoms

of psychiatric illness where none exists as in whistleblowing cases, has to perform complicated mental gymnastics to show

there is nothing wrong, however compelling the evidence that the plaintiff is genuinely ill.

If the patient shows signs that would normally be taken as symptoms of illness, the hired gun will interpret this as malingering.

An example:

"The prominent feature at this interview was what I consider to be overacting. The appearance of great anguish was so excessive

that I can only regard it as histrionic. It is my impression that [his complaints] are manufactured for the purposes of elaborating

upon what may have been a genuine disorder in the past.............In my opinion the state of the patient no longer meets

the criteria of PTSD, but rather impresses me more as malingering hysteria......"

Or he will provoke the patient and interpret their response as indicating hostility rather than legitimate illness. An example:

Claimant’s account of the examination: "I found Dr X’s attitude from the start to be provocative and intimidating.

He frequently smirked when I replied to his questions, and the whole interview with him was more in the nature of an interrogation.

At a later stage of the interview Dr X sat me in a chair and asked me to hunch up my shoulders. [Dr X has no orthopaedic qualifications

or expertise.] I indicated to him that I was in pain and that pushing down caused me pain. He asked me to hunch up my shoulders

again and I refused. He pushed down on my shoulders hard."

Dr X’s report of that examination: "He was bristling with anger and hostility. Although diagnosed as suffering from

major depression by Drs A and B, I have reservations about the diagnosis and note he failed to respond satisfactorily to any

treatment prescribed....."

That patient subsequently killed himself, which would seem to indicate Drs A and B were right about his major depression.

He was one of a series of suicides by patients who had been examined in this manner by Dr X, and while it would not be valid

to say without further evidence that Dr X’s examinations helped to cause those deaths, it is self-evident that such

abusive behaviour could hardly have helped.

Characteristics of hired guns

It appears a disproportionate number are male, although this may be an artefact. (One female psychiatrist featured prominently

in the recent series of articles in ‘The Australian’.) Regardless of gender, they are authoritarian, and in many

cases seem to have a genuine dislike and distrust of people who are in conflict with authority, as if being in such a situation

is evidence the patient must ipso facto be mad or bad. Most do forensic work most or all of the time, i.e. they do not have

ongoing contact with patients; and they work only for employers and/or insurance companies, never for plaintiffs. Some make

a lot of money. Unlike psychiatrists who cause other kinds of problems, they seem not to be prominent in medical politics,

but nevertheless are enough a part of the establishment to avoid any action being taken against them by e.g. the College of

Psychiatrists despite sometimes numerous complaints from victims and other psychiatrists.

Tactics of hired guns

The conduct of a typical examination is clearly aimed at avoiding the possibility of developing any rapport or empathy with

the patient - the reverse of a normal examination. The hired gun would no doubt deny that this is the intent, but it is hard

to find any other explanation. The process usually starts with secret briefings from the employer, usually inaccurate and

sometimes wildly misleading, which paint the patient as paranoid or impossible, and which the patient, unaware of their existence,

has no chance to refute. The psychiatrist will refuse to accept written information offered by the patient, or to allow a

support person into the interview; may arrive late with no explanation or apology; will not introduce himself or otherwise

make any attempt at normal politeness or making the patient comfortable; will use distractions such as wandering round the

room behind the patient, dropping noisy objects, or sitting with his feet up on the desk, eating his lunch. He will be hostile

and adversarial in manner, sometimes yelling at the patient, accusing them of lying, and may be verbally abusive, trying to

provoke an angry reaction which can then be used as ‘evidence’ of a personality disorder or malingering, depending

what is required.

Other common tactics are to use a standard report that is already on their word-processor, the hired gun simply filling in

the gaps. ‘Verballing’ patients is common, e.g. a throw-away, leading question at the end of the interview on

the lines of supposing they must have some bitterness about what has happened then becomes the focus of the report. One notorious

hired gun regularly uses a urine test for drugs, including prescribed drugs. The patient is asked what they are taking, and

the psychiatrist then says in his report that what the patient claimed to be taking or not taking is contradicted by the test

- additional ‘evidence’ that the patient is untruthful. Without a witness at the interview, or a tape-recording,

there is no independent evidence of what the patient really did say.

There is however one thing that hired guns almost never do - try to check the patient’s information with other, independent,

sources. Indeed I think it safe to say that someone who makes such an effort is not a hired gun.

Compliant courts

The over-riding problems with our courts are the adversarial system, which seems designed to hide rather than search for the

truth; and presiding judges and magistrates who might as well not be there, for all the good most do in keeping proceedings

and participants on the rails. I will not be making suggestions for overall reform of the court system, since Evan Whitton

will no doubt be covering that. I will just outline some of the problems. An enormous problem with the whole legal system

is the lack of ethics of most legal practitioners, as shown by countless examples of corruption in the system, and the almost

complete absence of lawyers prepared to blow the whistle on it. Other people can and do - police for example, often at enormous

personal risk - but lawyers almost never.

Before a plaintiff gets to a court hearing, they have to cope with their own lawyers’ incompetence and procrastination.

Few lawyers seem to have even basic competence in this area, a major problem being that their training removes any previous

tendencies to be goal-directed, so they become entirely process-directed. (Billing by the hour of course encourages this.)

Where they are going to end up, and when, seems not to be their concern. And because so many cases in the end are settled

(often very badly) out of court, most can’t get motivated to prepare a case until the day before the hearing if you’re

lucky, and often not until the day itself. These problems, and lack of money, have led a number of whistleblowers to do a

law degree themselves as the only means of finding an ethical and reliable lawyer, and many more to represent themselves without

any qualifications - when they seem to do rather better than most whistleblowers with lawyers. Certainly no worse.

Plaintiffs then have to cope with the tactics of large organisations with money, who can and do use the legal processes to

exhaust the plaintiffs’ emotional and financial resources, until they are forced to give up and go away, or to settle,

usually badly, just before a definitive hearing that could have set a precedent for other victims. The Westpac letters, and

the Justice Callinan issue, are examples of what is widespread and accepted practice. I have yet to hear of a judge taking

any action - or even saying anything - about these blatant delaying and other tactics. They seem quite happy to preside over

an abusive process that also, most conveniently, keeps matters of great public interest ‘sub-judice’ and safe

from public scrutiny until they are no longer news.

Plaintiffs also have to cope with their lawyers’ tendency to play for the other side - throwing cases, withdrawing from

them the day before they go to court, making deals, persuading bewildered victims to accept ruinously disadvantageous settlements,

losing documents, leaking information to the other side etc etc etc. Reasons for this behaviour range from corrupt collusion

to simply needing to clear a space in their diary; and of course collecting brownie points for their career.

Plaintiffs also have to cope with the vagaries of the system, and its tendency to compliance with the political and other

needs of the day. Name and detail suppression vary with the climate. A whole case in NSW involving a worker in a Minister’s

office was suppressed until after the last state election. One wonders how this could possibly be legally necessary, however

convenient politically. In the ‘Marsden case’, where Channel 7 is being sued over allegations on the ‘Witness’

program of underage sex the judge refused to suppress the (male) witnesses’ names. Had the witnesses been female I feel

that would have been what ‘Yes, Minister’ calls a courageous decision. There is also great reluctance to deal

with or even acknowledge some very odd occurrences in and around the system - crucial dates in court records obviously and

clumsily altered with white-out; blatant interference with witnesses; disappearing documents; and mysteriously reappearing

fire-arms. Judges don’t seem to want to know about such matters. No doubt some are in on the deals, whatever they may

be, but I suspect that most are simply reluctant to rock the boat. The needs of justice, and the community, take second place

to the desire for a quiet life.

Once in court, plaintiffs face major problems with bullying - an integral part of the adversarial system. Compliant judges

make no attempt to see fair play, as vulnerable plaintiffs are bullied by opposing counsel, cross-examined for days on end,

about anything at all, no matter how repetitive or irrelevant, regardless of their state of health - often until they collapse

and have to give up the case. Whether the plaintiff has suffered a brain injury that is the subject of the case, or is intellectually

disabled, psychiatrically or physically ill, or a child, seems to make no difference - judges still sit there and allow this

to happen. In one serious instance in NSW, a heavily-pregnant ex-police officer who had blown the whistle on a number of corrupt

colleagues testified before the Police Royal Commission. Her evidence lasted one day, justifying, one would think, half a

day of cross-examination on what she had said. She was then repetitively cross-examined as to ‘her credit’ (i.e.

her entire life history) by a series of lawyers representing each of the police she had named. This had been going on for

four days, with no end in sight, when she collapsed in the court, and went into premature labour, having developed pneumonia

and septicaemia. The baby, also suffering from septicaemia, was grossly premature, and is seriously and permanently disabled

as a result.

The legal system, albeit somewhat reluctantly, does recognise the existence of psychiatric injury, and that it may be legitimate

grounds for the award of damages. Many lawyers make profitable careers in this area. Yet psychiatric injuries are inflicted

by our court system every day - negligently, and sometimes wilfully as a deliberate strategy - and no-one is ever held accountable.

Battered plaintiffs can’t get an AVO against bullying barristers; and can’t sue a judge for neglect of his duty

of care to a vulnerable person with a disability. I hesitate to suggest more grist for the dysfunctional legal mill, but perhaps

such actions should become a reality?

Suggestions for reform

Psychiatric examinations of workers can be justified in some circumstances. Workers, like anyone else, can really become mentally

ill, and if this is affecting their work performance, or colleagues are genuinely concerned about them, it is useful to all

concerned - especially the patient - if there is a mechanism for dealing with it. An effective and ethical mechanism will

also avoid the problem of hired guns. The essentials are:

* the worker can be required, as a condition of continued employment, to have a psychiatric or other medical assessment

* the worker then sees a doctor of their choice. If they see a psychiatrist, they should be referred by their GP in the normal

way

* the employer can supply information to the patient’s GP/psychiatrist if they think it necessary, but this information

must be made available to the patient

* the psychiatrist should report on the diagnosis and necessary treatment, if any, to the patient’s GP in the normal

way. The only report to the employer should be a certificate of fitness or unfitness for work.

Psychiatric examinations of plaintiffs can also be justified in some circumstances, notably where the claim is one of psychiatric

injury. Where the claim is physical, and malingering is suspected, my own view is that covert surveillance etc is far more

appropriate than psychiatry. For psychiatric claims, the essentials can be divided into the immediately and easily possible,

and the ultimately desirable but more difficult:

* plaintiffs must have a choice of psychiatrist, usually from a list provided by the insurance company

* plaintiffs must be informed by the insurance company that they have the right to take a support person to the interview,

and that it is to their advantage to do so

* the psychiatrist must agree to allow a support person to accompany the plaintiff, and/or allow the interview to be recorded

* rudeness and abusive behaviour by a psychiatrist towards a plaintiff with a possible psychiatric injury must lead to his

removal from the insurance company’s list

* all psychiatric reports on a patient must be disclosed to the other side

The above measures would prevent most of the abuses. However, the ultimate aim must be to avoid ‘cash for comment’

pressures by making the court, rather than either or both sides, responsible for obtaining the necessary report. Again there

should be a panel of doctors, with the plaintiff able to choose. The advantages and savings of time, money and trauma are

so obvious, it is equally obvious that only a very powerful set of vested interests could keep the system going as it is.

Jean Lennane, April 2000

Dr Jean Lennane is a psychiatrist now working in private practice in Sydney. An active and vocal unionist during the fourteen

years she worked as director of drug and alcohol services at the Rozelle Hospital in Sydney, she was eventually sacked in

1990 for publicly criticising cuts to mental health and drug and alcohol services in the public health system. She then became

aware for the first time that the term ‘whistleblowing’ applied to what had happened, found what was then a small

body of research on the subject, and became involved in setting up the self-help organisation for whistleblowers now known

as Whistleblowers Australia, and adding to the now very substantial body of research.

Jean was founding president of WBA, then vice-president, and is now president again. Since it was founded in mid 1991, WBA

has become an influential and almost too respectable body, lobbying for a better deal for whistleblowers - that is, for employers,

public and private, to stop shooting the messenger. She has also become aware, from information from the hundreds of whistleblowers

who have contacted WBA over the years, that Australia is in deep trouble from widespread corruption, especially in our law-enforcement

agencies; also at all levels of our legal system, aided and abetted, regrettably, by some members of her own profession.

(SECTION 1983) 42 U.S.C. 1983. - Civil action for deprivation

of rights

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected,

any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges,

or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity,

or other proper proceeding for redress, except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission

taken in such officer's judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated

or declaratory relief was unavailable. For the purposes of this section, any Act of Congress applicable exclusively to the

District of Columbia shall be considered to be a statute of the District of Columbia

"Citizens may resist unlawful arrest to the point of taking an arresting officer's life if necessary." Plummer v.

State, 136 Ind. 306. Upheld: John Bad Elk v. U.S., 177 U.S. 529. The U.S. Supreme Court stated, "Where the officer

is killed in the course of the disorder which naturally accompanies an attempted arrest that is resisted, the law looks with

very different eyes upon the transaction, when the officer had the right to make the arrest, from what it does if the officer

had no right. What may be murder in the first case might be nothing more than manslaughter in the other, or the facts might

show that no offense had been committed."

"An arrest made with a defective warrant, or one issued without affidavit, or one that falls to allege a crime is

within jurisdiction, and one who is being arrested, may resist arrest and break away. If the arresting officer is killed

by one who is so resisting, the killing will be no more than an involuntary manslaughter." Housh v. People, 75 111, 491;

reaffirmed and quoted in State v. Leach, 7 Conn. 452; State v. Gleason, 32 Kan. 245; Ballard v. State, 43 Ohio 349; State

v. Rousseau, 241 P. 2d 447; State v. Spaulding, 34 Minn. 3621.

"When a person, being without fault, is in a place where he has a right to be, is violently assaulted, he may, without

retreating, repel by force, and if, in the reasonable exercise of his right of self defense, his assailant is killed, he is

justiciable." Runyan v. State, 57 Ind. 80; Miller v. State, 74 Ind. 1. "These principles apply as well to an officer

attempting to make an arrest, who abuses his authority and transcends the bounds thereof by the use of unnecessary force and

violence, as they do to a private individual who unlawfully used such force and violence." Jones v. State, 26 Tex. App.

1; Beaverts v. State, 4 Tex. App. 1 75; Skidmore v. State, 43 Tex. 93, 903.

-CITE-

18 USC Sec. 241

01/06/97

-EXPCITE-

TITLE 18 - CRIMES AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

PART

I - CRIMES

CHAPTER 13 - CIVIL RIGHTS

-HEAD-

Sec. 241. Conspiracy against rights

-STATUTE-

If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress, threaten,

or

intimidate any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth,

Possession, or District in the free exercise or enjoyment

of any

right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of

the United States, or because of his having

so exercised the same;

or

If two or more persons go in disguise on the highway, or on the

premises of another,

with intent to prevent or hinder his free

exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege so secured -

They shall

be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than

ten years, or both;

and if death results from the acts committed

in

violation of this section or if such acts include kidnapping or an

attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse or

an attempt to commit

aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill,

they shall be fined

under this title or imprisoned

for any term of years or for life,

or both, or may be sentenced to death.

-SOURCE-

(June 25, 1948, ch. 645, 62 Stat. 696; Apr. 11,

1968, Pub. L.

90-284, title I, Sec. 103(a), 82 Stat. 75; Nov. 18, 1988, Pub. L.

100-690, title VII, Sec. 7018(a),

(b)(1), 102 Stat. 4396; Sept. 13,

1994, Pub. L. 103-322, title VI, Sec. 60006(a), title XXXII, Sec.

320103(a), 320201(a),

title XXXIII, Sec. 330016(1)(L), 108 Stat.

1970, 2109, 2113, 2147; Oct. 11, 1996, Pub. L. 104-294, title VI,

Sec.

604(b)(14)(A), 607(a), 110 Stat. 3507, 3511.)

-MISC1-

HISTORICAL AND REVISION NOTES

Based on title

18, U.S.C., 1940 ed., Sec. 51 (Mar. 4, 1909, ch.

321, Sec. 19, 35 Stat. 1092).

Clause making conspirator ineligible

to hold office was omitted

as incongruous because it attaches ineligibility to hold office to

a person who may be

a private citizen and who was convicted of

conspiracy to violate a specific statute. There seems to be no

reason for

imposing such a penalty in the case of one individual

crime, in view of the fact that other crimes do not carry such a

severe consequence. The experience of the Department of Justice is

that this unusual penalty has been an obstacle

to successful

prosecutions for violations of the act.

Mandatory punishment provision was rephrased in the alternative.

Minor changes in phraseology were made.

AMENDMENTS

1996 - Pub. L. 104-294, Sec. 607(a), substituted ''any State,

Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District'' for ''any State,

Territory, or District'' in first par.

Pub.

L. 104-294, Sec. 604(b)(14)(A), repealed Pub. L. 103-322,

Sec. 320103(a)(1). See 1994 Amendment note below.

1994 -

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 330016(1)(L), substituted ''They

shall be fined under this title'' for ''They shall be fined not

more than $10,000'' in third par.

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 320201(a), substituted ''person in any

State'' for ''inhabitant

of any State'' in first par.

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 320103(a)(2)-(4), in third par.,

substituted ''results from the

acts committed in violation of this

section or if such acts include kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap,

aggravated

sexual abuse or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual

abuse, or an attempt to kill, they shall be fined under this title

or imprisoned for any term of years or for life, or both'' for

''results, they shall be subject to imprisonment for

any term of

years or for life''.

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 320103(a)(1), which provided for amendment

identical to

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 330016(1)(L), above, was

repealed by Pub. L. 104-294, Sec. 604(b)(14)(A).

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec.

60006(a), substituted '', or may be

sentenced to death.'' for period at end of third par.

1988 - Pub. L. 100-690 struck

out ''of citizens'' after

''rights'' in section catchline and substituted ''inhabitant of any

State, Territory, or

District'' for ''citizen'' in text.

1968 - Pub. L. 90-284 increased limitation on fines from $5,000

to $10,000 and

provided for imprisonment for any term of years or

for life when death results.

EFFECTIVE DATE OF 1996 AMENDMENT

Amendment

by section 604(b)(14)(A) of Pub. L. 104-294 effective

Sept. 13, 1994, see section 604(d) of Pub. L. 104-294, set out as

a

note under section 13 of this title.

SHORT TITLE OF 1996 AMENDMENT

Pub. L. 104-155, Sec. 1, July 3, 1996, 110

Stat. 1392, provided

that: ''This Act (amending section 247 of this title and section

10602 of Title 42, The Public

Health and Welfare, enacting

provisions set out as a note under section 247 of this title, and

amending provisions

set out as a note under section 534 of Title

28, Judiciary and Judicial Procedure) may be cited as the 'Church

Arson

Prevention Act of 1996'.''

-CITE-

18 USC Sec. 242 01/06/97

-EXPCITE-

TITLE 18 - CRIMES AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

PART

I - CRIMES

CHAPTER 13 - CIVIL RIGHTS

-HEAD-

Sec. 242. Deprivation of rights under color of law

-STATUTE-

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation,

or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory,

Commonwealth, Possession, or District

to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the

Constitution or laws of the

United States, or to different

punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being

an alien, or by reason

of his color, or race, than are prescribed

for the punishment of citizens, shall be fined under this title or

imprisoned

not more than one year, or both; and if bodily injury

results from the acts committed in violation of this section or

if

such acts include the use, attempted use, or threatened use of a

dangerous weapon, explosives, or fire, shall be

fined under this

title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and if death

results from the acts committed

in violation of this section or if

such acts include kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated

sexual abuse,

or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or

an attempt to kill, shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned

for any term of years or for life, or both, or may be sentenced to

death.

-SOURCE-

(June 25, 1948, ch. 645, 62 Stat. 696; Apr. 11,

1968, Pub. L.

90-284, title I, Sec. 103(b), 82 Stat. 75; Nov. 18, 1988, Pub. L.

100-690, title VII, Sec. 7019, 102

Stat. 4396; Sept. 13, 1994, Pub.

L. 103-322, title VI, Sec. 60006(b), title XXXII, Sec. 320103(b),

320201(b), title

XXXIII, Sec. 330016(1)(H), 108 Stat. 1970, 2109,

2113, 2147; Oct. 11, 1996, Pub. L. 104-294, title VI, Sec.

604(b)(14)(B),

607(a), 110 Stat. 3507, 3511.)

-MISC1-

HISTORICAL AND REVISION NOTES

Based on title

18, U.S.C., 1940 ed., Sec. 52 (Mar. 4, 1909, ch.

321, Sec. 20, 35 Stat. 1092).

Reference to persons causing or procuring

was omitted as

unnecessary in view of definition of ''principal'' in section 2 of

this title.

A minor change was

made in phraseology.

AMENDMENTS

1996 - Pub. L. 104-294, Sec. 607(a), substituted ''any State,

Territory, Commonwealth,

Possession, or District'' for ''any State,

Territory, or District''.

Pub. L. 104-294, Sec. 604(b)(14)(B), repealed

Pub. L. 103-322,

Sec. 320103(b)(1). See 1994 Amendment note below.

1994 - Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 330016(1)(H), substituted

''shall be

fined under this title'' for ''shall be fined not more than

$1,000'' after ''citizens,''.

Pub. L. 103-322,

Sec. 320201(b), substituted ''any person in any

State'' for ''any inhabitant of any State'' and ''on account of

such

person'' for ''on account of such inhabitant''.

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 320103(b)(2)-(5), substituted ''bodily

injury

results from the acts committed in violation of this section

or if such acts include the use, attempted use, or threatened

use

of a dangerous weapon, explosives, or fire, shall be fined under

this title or imprisoned not more than ten years,

or both; and if

death results from the acts committed in violation of this section

or if such acts include kidnapping

or an attempt to kidnap,

aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual

abuse, or an attempt to

kill, shall be fined under this title, or

imprisoned for any term of years or for life, or both'' for

''bodily injury

results shall be fined under this title or

imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and if death results

shall

be subject to imprisonment for any term of years or for

life''.

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 320103(b)(1), which provided

for amendment

identical to Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 330016(1)(H), above, was

repealed by Pub. L. 104-294, Sec. 604(b)(14)(B).

Pub. L. 103-322, Sec. 60006(b), inserted before period at end '',

or may be sentenced to death''.

1988 - Pub.

L. 100-690 inserted ''and if bodily injury results

shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten

years,

or both;'' after ''or both;''.

1968 - Pub. L. 90-284 provided for imprisonment for any term of

years or for life when

death results.

EFFECTIVE DATE OF 1996 AMENDMENT

Amendment by section 604(b)(14)(B) of Pub. L. 104-294 effective

Sept.

13, 1994, see section 604(d) of Pub. L. 104-294, set out as a

note under section 13 of this title.

-CROSS-

CROSS REFERENCES

Civil action for deprivation

of rights, see section 1983 of Title

42, The Public Health and Welfare.

Equal rights under the law, see section 1981

of Title 42.

Minor offenses tried by United States magistrate judges as

excluding offenses punishable under this section,

see section 3401

of this title.

Proceedings in vindication of civil rights, see section 1988 of

Title 42, The

Public Health and Welfare.

-CROSS-

CROSS REFERENCES

Action for neglect to

prevent, see section 1986 of Title 42, The

Public Health and Welfare.

Conspiracy to commit offense or to defraud United

States, see

section 371 of this title.

Conspiracy to interfere with civil rights, see section 1985 of

Title 42,

The Public Health and Welfare.

Proceedings in vindication of civil rights, see section 1988 of

Title 42.

|

|

|

At the conclusion of its service, a special grand

jury is authorized under 18 U.S.C. § 3333, by a majority vote of its members, to submit to the district court, potentially

for public release, a grand jury report, which must concern either: (1) noncriminal misconduct, malfeasance, or misfeasance

in office involving organized crime activity by an appointed public officer or employee, as the basis for a recommendation

for removal or disciplinary action; or (2) organized crime conditions in the district, without however being critical of any

identified person. ("Public officer or employee" is defined broadly in 18 U.S.C. § 3333(f) to include Federal, State and local

officials.)

Upon receiving a report from a special grand jury,

the district court must examine it, together with the minutes of the special grand jury, and accept it, for eventual filing

as a public record, if the report is: (1) one of the two types authorized by 18 U.S.C. § 3333(a); (2) based upon facts discovered

in the course of an authorized criminal investigation; (3) supported by a preponderance of the evidence; and (4) if each public

officer or employee named in the report was afforded a reasonable opportunity to testify and present witnesses on his/her

own behalf before the special grand jury, prior to its filing the report. (It would seem that 18 U.S.C. § 3333(a) necessitates

a recording of the proceedings if a special grand jury may issue a grand jury report.)

The wording and the legislative history of 18 U.S.C.

§§ 3332(a) and 3333(b)(1) indicate that a special grand jury should not investigate for the sole purpose of writing a report;

the report must emanate from the criminal investigation. At bottom, then, a special grand jury functions essentially like

a regular grand jury. It is only after the "completion" of the criminal investigation, when the time is near for discharging

the jury, that a report may be submitted to the court under 18 U.S.C. § 3333(a). The grand jury will by that time have exhausted

all investigative leads and have found all appropriate indictments.

The "misconduct," "malfeasance," or "misfeasance"

that may be the subject of a report (provided it is related to organized criminal activity) must, to some degree, involve

willful wrongdoing as distinguished from mere inaction or lack of diligence on the part of the public official. Nonfeasance

in office, however, if it is of such serious dimensions as to be equatable with misconduct, may be a basis for a special grand

jury report. See S.Rep. No. 617, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. (1969), reprinted in 1970 U.S.C.C.A.N. 4007.

Reports involving public officials must connect

"misconduct," "malfeasance," or "misfeasance" with "organized criminal activity." "Organized criminal activity" should be

interpreted as being much broader than "organized crime;" it includes "any criminal activity collectively undertaken." This

statement is based upon the legislative history of 18 U.S.C. § 3503(a), not of 18 U.S.C. § 3333, but both sections were part

of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970, making it logical to construe the term the same way for both sections. See

116 Cong. Rec. 35,290 (October 7, 1970).

Before the district court may enter as a public

record a special grand jury report concerning appointed public officers or employees, a complex procedure must be followed

as set down in 18 U.S.C. § 3333(c).

If a court decides that a report submitted to it

by a special grand jury regarding a public officer or employee does not comply with the law, the court may seal the report

and keep it secret or, for remedial purposes, order the same grand jury to take additional testimony. For purposes of taking

additional testimony, a special grand jury may be extended to serve for longer than thirty-six months (but this is the only

exception to the thirty-six months limitation).

If the district court feels that the filing of a

special grand jury report as a public record would prejudice the fair consideration of a pending criminal matter, the court

is authorized under 18 U.S.C. § 3333(d) to keep the report sealed during the pendency of that matter. Sealed for such a reason,

the report would not be subject to subpoena.

When appropriate, United States Attorneys will deliver

copies of grand jury reports, together with the appendices, to the governmental bodies having jurisdiction to discipline the

appointed officers and employees whose involvement in "organized criminal activity" is the subject of the report. See

18 U.S.C. § 3333(c)(3). (The prospect of such disciplinary action does not prevent the officer's or employee's being compelled

to testify under a grant of immunity.) See In re Reno, 331 F. Supp. 507 (E.D. Mich. 1971).

"Because of what appears to be a lawful command on the surface, many Citizens, because of respect for the law, are cunningly

coerced into waiving their rights due to ignorance."

U.S. v. Minker, 350 U.S. 179, 187

CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS:

Boyd v. United, 116 U.S. 616

at 635 (1885)

Justice Bradley, "It may be that it is the obnoxious thing in its

mildest form; but illegitimate and unconstitutional practices get their first footing in that way; namely, by silent approaches

and slight deviations from legal modes of procedure. This can only be obviated by adhering to the rule that constitutional

provisions for the security of persons and property should be liberally construed. A close and literal construction

deprives them of half their efficacy, and leads to gradual depreciation of the right, as if it consisted more in sound than

in substance. It is the duty of the Courts to be watchful for the Constitutional Rights of the Citizens, and against

any stealthy encroachments thereon. Their motto should be Obsta Principiis."

Downs v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244

(1901)

"It will be an evil day for American Liberty if the theory of a

government outside supreme law finds lodgement in our constitutional jurisprudence. No higher duty rests upon this Court

than to exert its full authority to prevent all violations of the principles of the Constitution."

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364

U.S. 155 (1966), cited also in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649.644

"Constitutional 'rights' would be of little value if they

could be indirectly denied."

Juliard v. Greeman,

110 U.S. 421 (1884)

Supreme Court Justice Field, "There is no such thing as

a power of inherent sovereignty in the government of the United States... In this country, sovereignty resides in the people,

and Congress can exercise power which they have not, by their Constitution, entrusted to it. All else is withheld."

Mallowy v. Hogan, 378

U.S. 1

"All rights and safeguards contained in the first eight

amendments to the federal Constitution are equally applicable."

Miranda v. Arizona,

384 U.S. 426, 491; 86 S. Ct. 1603

"Where rights secured by the Constitution are involved,

there can be no 'rule making' or legislation which would abrogate them."

Norton v. Shelby County,

118 U.S. 425 p. 442

"An unconstitutional act is not law; it confers no rights;

it imposes no duties; affords no protection; it creates no office; it is in legal contemplation, as inoperative as though

it had never been passed."

Perez v. Brownell, 356

U.S. 44, 7; 8 S. Ct. 568, 2 L. Ed. 2d 603 (1958)

"...in our country the people are sovereign and the government

cannot sever its relationship to them by taking away their citizenship."

Sherar v. Cullen, 481

F. 2d 946 (1973)

"There can be no sanction or penalty imposed upon one because

of his exercise of constitutional rights."

Simmons v. United States,

390 U.S. 377 (1968)

"The claim and exercise of a Constitution right cannot

be converted into a crime"... "a denial of them would be a denial of due process of law".

Warnock v. Pecos County,

Texas., 88 F3d 341 (5th Cir. 1996)

Eleventh Amendment does not protect state officials from

claims for prospective relief when it is alleged that state officials acted in violation of federal law.

CORRUPTION OF AUTHORITY:

Burton v. United States, 202

U.S. 344, 26 S. Ct. 688 50 L.Ed 1057

United States Senator convicted of, among other things, bribery.

Butz v. Economou, 98 S. Ct. 2894 (1978);

United States v. Lee, 106 U.S. at 220, 1 S. Ct. at 261 (1882)

"No man [or woman] in this country is so

high that he is above the law. No officer of the law may set that law at defiance with impunity. All the officers

of the government from the highest to the lowest, are creatures of the law, and are bound to obey it."

*Cannon v. Commission on Judicial Qualifications,

(1975) 14 Cal. 3d 678, 694

Acts in excess of judicial authority constitutes misconduct,

particularly where a judge deliberately disregards the requirements of fairness and due process.

*Geiler v. Commission on Judicial Qualifications,

(1973) 10 Cal.3d 270, 286

Society's commitment to institutional justice requires

that judges be solicitous of the rights of persons who come before the court.

*Gonzalez v. Commission on Judicial Performance,

(1983) 33 Cal. 3d 359, 371, 374

Acts in excess of judicial authority constitutes misconduct,

particularly where a judge deliberately disregards the requirements of fairness and due process.

Olmstad v. United States,

(1928) 277 U.S. 438

"Crime is contagious. If the Government becomes a

lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for law; it invites every man to become a law unto himself; it invites anarchy."

Owen v. City of Independence

"The innocent individual who is harmed by an abuse of governmental

authority is assured that he will be compensated for his injury."

Perry v. United States,

204 U.S. 330, 358

"I do not understand the government to contend that it

is any less bound by the obligation than a private individual would be..." "It is not the function of our government

to keep the citizen from falling into error; it is the function of the citizen to keep the government from falling into error."

*Ryan v. Commission on Judicial Performance,

(1988) 45 Cal. 3d 518, 533

Before sending a person to jail for contempt or imposing

a fine, judges are required to provide due process of law, including strict adherence to the procedural requirements

contained in the Code of Civil Procedure. Ignorance of these procedures is not a mitigating but an aggravating factor.

U.S. v. Lee, 106 U.S.

196, 220 1 S. Ct. 240, 261, 27 L. Ed 171 (1882)

"No man in this country is so high that he is above the

law. No officer of the law may set that law at defiance, with impunity. All the officers of the government, from

the highest to the lowest, are creatures of the law are bound to obey it."

"It is the only supreme power in our system of government,

and every man who, by accepting office participates in its functions, is only the more strongly bound to submit to that supremacy,

and to observe the limitations which it imposes on the exercise of the authority which it gives."

Warnock v. Pecos County, Texas,

88 F3d 341 (5th Cir. 1996)

Eleventh Amendment does not protect state officials from claims

for prospective relief when it is alleged that state officials acted in violation of federal law.

DISMISSAL OF SUIT:

Note: [Copied verbiage; we are not lawyers.] It

can be argued that to dismiss a civil rights action or other lawsuit in which a serious factual pattern or allegation of a

cause of action has been made would itself be violating of procedural due process as it would deprive a pro se litigant of

equal protection of the law vis a vis a party who is represented by counsel.

Also, see Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 60 - Relief

from Judgment or Order (a) Clerical Mistakes and (b) Mistakes; Inadvertence; Excusable Neglect; Newly Discovered Evidence;

Fraud, etc.

Warnock v. Pecos County, Texas,

88 F3d 341 (5th Cir. 1996)

Eleventh Amendment does not protect state officials from claims

for prospective relief when it is alleged that state officials acted in violation of federal law.

Walter Process Equipment v. Food

Machinery, 382 U.S. 172 (1965)

... in a "motion to dismiss, the material allegations of the complaint

are taken as admitted". From this vantage point, courts are reluctant to dismiss complaints unless it appears the plaintiff

can prove no set of facts in support of his claim which would entitle him to relief (see Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S.

41 (1957)).

EQUAL PROTECTION UNDER THE LAW

Cochran v. Kansas, 316 U.S. 255, 257-258

(1942)

"However inept Cochran's choice of words,

he has set out allegations supported by affidavits, and nowhere denied, that Kansas refused him privileges of appeal which

it afforded to others. *** The State properly concedes that if the alleged facts pertaining to the suppression of Cochran's

appeal were disclosed as being true, ... there would be no question but that there was a violation of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment."

Duncan v. Missouri, 152 U.S. 377,

382 (1894)

Due process of law and the equal protection

of the laws are secured if the laws operate on all alike, and do not subject the individual to an arbitrary exercise of the

powers of government."

Giozza v. Tiernan, 148 U.S. 657, 662

(1893), Citations Omitted

"Undoubtedly it (the Fourteenth Amendment)

forbids any arbitrary deprivation of life, liberty or property, and secures equal protection to all under like circumstances

in the enjoyment of their rights... It is enough that there is no discrimination in favor of one as against another of the

same class. ...And due process of law within the meaning of the [Fifth and Fourteenth] amendment is secured if the laws

operate on all alike, and do not subject the individual to an arbitrary exercise of the powers of government."

Kentucky Railroad Tax Cases, 115 U.S.

321, 337 (1885)

"The rule of equality... requires the

same means and methods to be applied impartially to all the constitutents of each class, so that the law shall operate equally

and uniformly upon all persons in similar circumstances".